Uranium Production in the Gunnison Basin

Introduction By: Luke Danielson and Elizabeth Hartson

Prior to World War II, there was little demand for uranium, and as a result, very little uranium mining anywhere in the world. The nuclear explosions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the deep concern about the nuclear arms race once the Soviet Union had joined the nuclear “club” created great pressure to explore for and locate exploitable reserves of uranium.

As other uses of uranium emerged, from powering ships to generating electricity for the civilian power grid, the importance of this mineral continued to grow. Government had a central role in this process and provided a variety of incentives to encourage the exploration for and production of uranium. And since government controlled the essential process of uranium enrichment, it was effectively the sole purchaser of uranium, and could ensure that sellers received a price that would encourage the expansion of the industry. (Tippitt 1954). Click Here to Read More

This created a considerable “uranium boom,” with many of the characteristics of the gold, silver, coal and other resource production that have played so great a part in the history of this region. The Colorado Plateau area of Utah, New Mexico, Arizona and Colorado turned out to be a major center of production. The Gunnison Basin turned out to contain significant uranium deposits.

In 1954, a discovery was made in Saguache County on a ranch owned by Irving S. Youmans 18 miles southeast of Gunnison that would ignite the uranium boom on the area. Youmans pointed out an odd yellow rock to a group of eight men hailing from Colorado Springs and Pueblo. The men took out a Geiger counter and registered a spike in radioactivity associated with the rock (Hayes 1967). Samples sent to Denver and Grand Junction assayed at 2 percent uranium concentrations in a mineral called carnotite, and the rest is history. This group of eight men founded the Los Ochos Mining Company, which came to be made up of some 31 claims that measured 600 feet by 1,800 feet each. By 1955, these claims had been sold to the Gunnison Mining Company, a new branch of the Grand Junction-based Thornburg Company. The Gunnison Mining Company later founded a uranium mill in Gunnison, and also acquired claims from the MAT Mining Company to the tune of nearly a half-million dollars, making it one of the largest mining transactions in the Gunnison area (Hayes 1967).

In 1954, a discovery was made in Saguache County on a ranch owned by Irving S. Youmans 18 miles southeast of Gunnison that would ignite the uranium boom on the area. Youmans pointed out an odd yellow rock to a group of eight men hailing from Colorado Springs and Pueblo. The men took out a Geiger counter and registered a spike in radioactivity associated with the rock (Hayes 1967). Samples sent to Denver and Grand Junction assayed at 2 percent uranium concentrations in a mineral called carnotite, and the rest is history. This group of eight men founded the Los Ochos Mining Company, which came to be made up of some 31 claims that measured 600 feet by 1,800 feet each. By 1955, these claims had been sold to the Gunnison Mining Company, a new branch of the Grand Junction-based Thornburg Company. The Gunnison Mining Company later founded a uranium mill in Gunnison, and also acquired claims from the MAT Mining Company to the tune of nearly a half-million dollars, making it one of the largest mining transactions in the Gunnison area (Hayes 1967).

The significant federal incentives driving uranium prospecting at the time are the very foundations of this story. Commercial concentrations of uranium ore were regulated, and primarily purchased, by the United States Atomic Energy Commission. In fact, the Commission had a unique control of the uranium market: it outlined all regulations for the sale of uranium ore, as well as the licensing procedures, prices, bonuses, and the special allowances. As such, Circular 5 of the Commission regulation set minimum prices for uranium ore– $1.50 per 0.10 percent to $3.50 per 0.20 percent and higher– in the Colorado Plateau Region (Hayes 1967). Discovery of new high-quality deposits was also incentivized with a bonus of $10,000 for the discovery and production of the first 20 tons of 20%-assaying uranium ore. This created a boom with prospectors staking claims on public lands, using portable Geiger counters to identify potential sites.

This boom drove development of several major uranium-producing prospects and mines in the Gunnison watershed. The formation on the Youmans ranch was named the Los Ochos Fault after the original prospectors, and the underground mine that was eventually excavated on that site can be found under the names Los Ochos Mine or, more commonly, Thornburg Mine at coordinates -106.74701, 38.36944 (WGS84, Conservation Division Files USGS 2017). The Thornburg Mine and a few associated mines under the same listing, including the East Mine and a second adit known as T-2, were all primarily producers of uranium (Conservation Division Files USGS 2017).

Also operated within the Los Ochos Fault was the nearby Elisha Group, consisting of two trench mines at coordinates -106.76861, 38.30375 which also produced uranium (WGS84, Conservation Division Files USGS 2017).

The Pitch Mine, likely named for the uranium ore pitchblende found there, was a major producer of uranium and vanadium located on Marshall Pass in Saguache County within the Gunnison watershed at coordinates -106.30088, 38.4075 (WGS84, Conservation Division Files USGS 2017, “Pitch Mine”). After the location was discovered in 1955, the Pitch Mine produced approximately 100,000 tons of ore containing a million pounds of uranium concentrate, and some of this ore was as high as 10-15% uranium-308 (Conservation Division Files USGS 2017). Underground mining took place at the Pitch Mine site through 1972, but its story didn’t end there, as we’ll see later. Finally, the White Earth District was prospected, but seemingly not mined, near Cebolla Creek prior to 1961 at coordinates -107.05342, 38.255 (WGS84); primary products include iron, manganese, and vermiculite, with uranium, thorium, and vanadium listed as tertiary products (Conservation Division Files, USGS 2017).

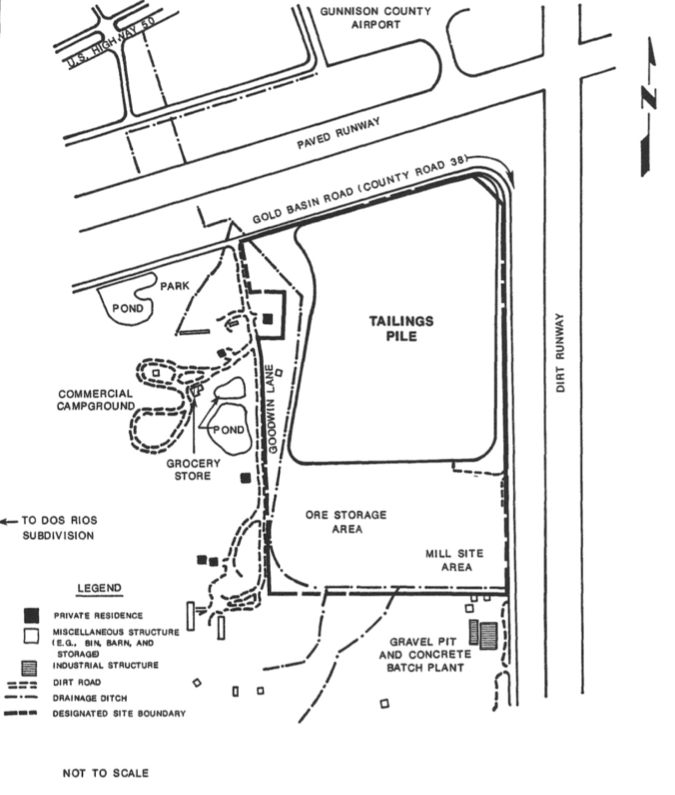

In March 1958, the Gunnison Mining Company’s processing mill came online, southwest of Gunnison located near where the airport now stands (Hayes 1967, Environmental Assessment 1992). It appears the Thornburg Mine and its associated tunnels were the primary suppliers for this mill, which extracted uranium through sulfuric acid leaching. This process necessitated the construction of a tailings pond for contaminated water. Depletion of ore reserves in the Thornburg Mine forced the Gunnison Mill to close its doors in 1962 (Hayes 1967).

From US Department of Energy, 1992

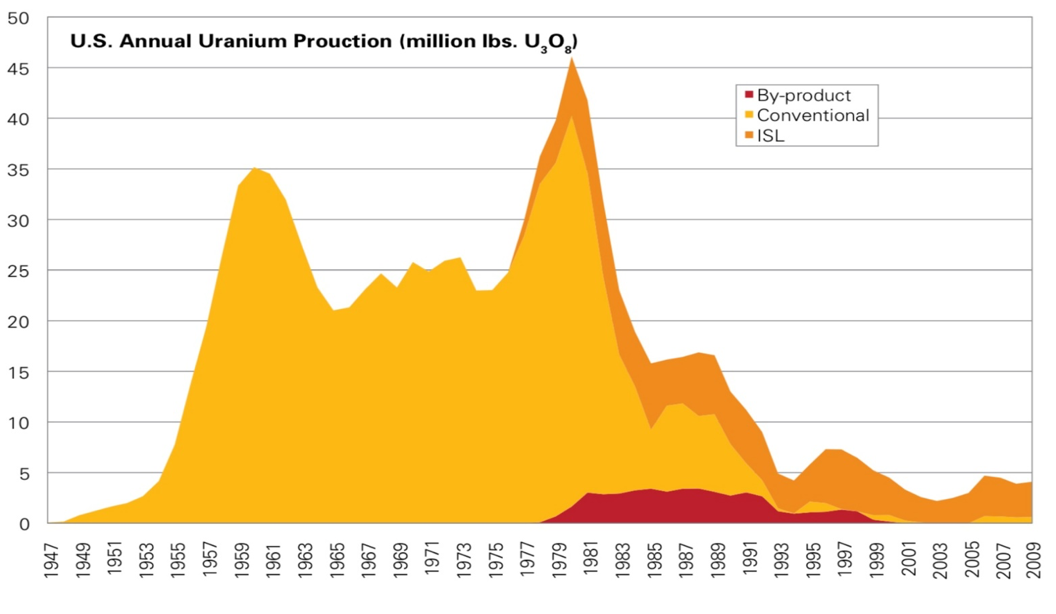

In general, as has so often happened with government subsidy programs for mineral production, the uranium incentive program overshot its mark, leading to an oversupply and glut of uranium in federal hands. The federal government phased out many of its subsidies for uranium production, and many of the uranium mines and mills that had sprung up closed in the 1960s, leaving a considerable environmental legacy.

Table 1: The uranium boom in numbers (adapted from Fettus and McKinzie 2012).

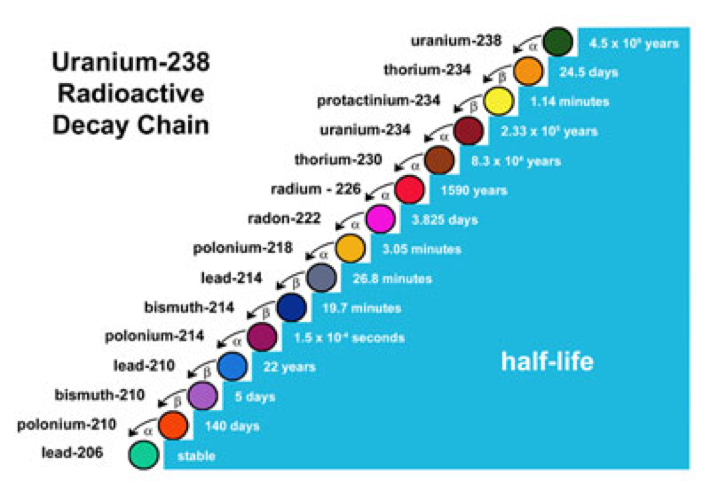

Uranium mill tailings remain radioactive. Uranium-238, the principal isotope of uranium, decays over time into a series of other radioactive materials. This decay chain is called the “uranium series” or “radium series”. Any ore containing uranium-238 eventually produces radioactive isotopes of astatine, bismuth, lead, polonium, protactinium, radium, radon, thallium, and thorium. The series terminates with a stable and non-radioactive element, lead-206. (Radioactive Decay, Teach Nuclear 2018).

The uranium-238 decay series (New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources 2018).

In the 1970s, it became clear that the government effort to stimulate uranium production had left the West with a legacy of hazardous uranium mill tailings at over 30 sites, one of which turned out to be in Gunnison.

The response was the 1978 Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act (UMTCRA) Remedial investigations in 1981 identified the Gunnison mill’s tailings pile as a threat to the public, citing radon gas emanating from the dry tailings, along with potential for gamma radiation exposure by windblown particles, contaminated soil, groundwater, or food grown on the contaminated soil (Ford, Bacon, & Davis Utah Inc. 1981, US DOE 1992). In fact, groundwater already had been contaminated by cadmium and uranium for 22 downstream homes (US DOE 1992, US DOE 1995). Initial investigations looked into the possibility of returning the mill tailings to the mine, but this was deemed unfeasible due to distance to the mine and the collapse of mine workings (DOE 1992).

Figure 1: The collapse of Los Ochos Mine, also known as the Thornburg mine, as well as its considerable distance from the Gunnison Mill, made returning the mill tailings to the mine site impossible. (Image from QKC 2009)

Figure 1: The collapse of Los Ochos Mine, also known as the Thornburg mine, as well as its considerable distance from the Gunnison Mill, made returning the mill tailings to the mine site impossible. (Image from QKC 2009)

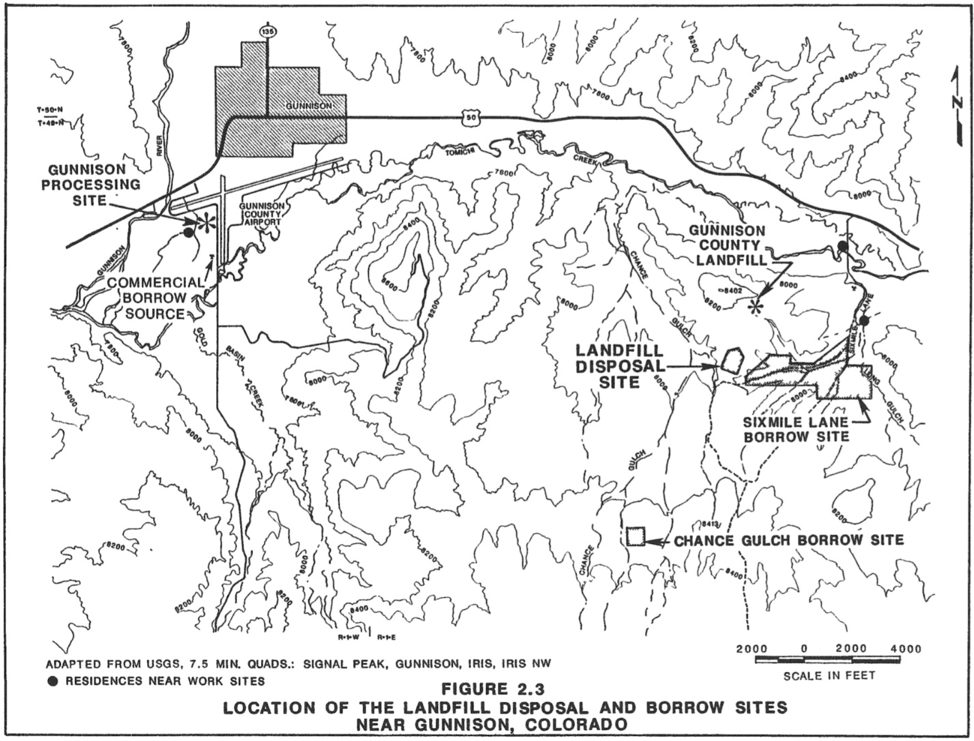

After an Alternative Site Selection Process (ASSP), the Department of Energy (DOE) instead oversaw the removal of an estimated 718,900 cubic yards of contaminated material to a 92-acre disposal site on nearby Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands, which the BLM ceded to the DOE, near the present Gunnison landfill, to which the tailings would be transported by truck. This project was completed in the mid-1990s, and in 1998, a long-term surveillance plan by the DOE stipulated annual monitoring of groundwater near the disposal cell until 2001, at which point surveillance would continue every five years (US DOE 2012). The 2011 onsite follow-up found the cell and all surface water diversion structures to be in excellent condition, with uranium levels well below Safe Drinking Water Act standards (US DOE 2012).

Figure 2: The DOE decided to dispose of the tailings on a 92-acre BLM plot near the Gunnison landfill. “Borrow sites” indicate locations where rocks, used to line the disposal cell, were sourced (US DOE 1992).

Figure 2: The DOE decided to dispose of the tailings on a 92-acre BLM plot near the Gunnison landfill. “Borrow sites” indicate locations where rocks, used to line the disposal cell, were sourced (US DOE 1992).

Uranium Resurgence

As is clear from Table 1 above, there was a uranium boom in the 1950s, followed by a “bust” in the 1960s. But growth of demand, and expectations of further growth of the nuclear electrical power industry, led to a new “boom” by the late 1970s.

Once again, the Gunnison Basin was affected. Homestake Mining Company purchased the aforementioned Pitch Mine site on Marshall Pass, and proposed in an Environmental Assessment (EA) to expand the Pitch Mine into a large open pit uranium mine and build an associated uranium mill.

Given the past experience with uranium mining and milling in the area, this proposal was very controversial and was opposed by a number of local and regional environmental organizations. After preparing its initial EA for the Pitch Project, Homestake was required in 1978 to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) before it could commence milling and processing. So, in 1979, Homestake commenced full-scale mining to stockpile ore, awaiting final approval of the EIS and its Radioactive Source Materials License.

Opponents to Homestake’s plan contested the EIS by filing an administrative appeal with the U.S. Forest Service. So, in what was one of the first high profile mediation efforts at an American mine site, Homestake and its opponents entered into an attempt to resolve their differences in 1982. To the surprise of many, the opponents succeeded (Watson and Danielson 1983). Under the mediated settlement, the company agreed not to build a uranium mill at the project site, and to eschew development of low-grade ore. It would instead mine the high-grade ore and ship it to a mill in New Mexico, which was underway by 1982.

In the meantime, the great uranium boom of the late 1970s ended in the wake of the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in March 1979. Homestake undoubtedly saved a great deal of capital through its agreement not to develop a Marshall Pass mill. There were several years of mining high-grade ore at Pitch, but this operation came to an end in the 1980s. According to Homestake’s contact person, Dave Wykoff, a combination of dropping uranium prices and safety concerns after a wall failure in the North Pit contributed to the eventual closure of the mine on April 29, 1983. Though the initial plan was to use the South Pit’s waste rock to backfill the North Pit, the early closure of the mine meant these plans did not come to fruition. Currently, the North Pit contains a pit lake, and the South Pit is a free draining sidehill cut with no water on the pit bottom.

Overview of the Pitch Mine in 2018 showing the North Pit near right center with the pit lake at its base, via Google Earth.

Today, national uranium production is far below its historic peak, and most of this production is through a new technology called in situ leaching or lixiviation rather than the traditional mining methods.

As of this writing, the Pitch Mine is the only uranium mine in the Upper Gunnison Basin that has an active mining permit. However, though its permit is considered active, the principal activity at the site is reclamation work.

There are currently no active uranium mining or processing operations in Gunnison County. The Los Ochos uranium mine site is being assessed for remediation by the Department of Energy, the Bureau of Land Management and the Inactive Mines Program of the Colorado Division of Reclamation Mining and Safety.

Figure 3: Legacy of the uranium boom: the final Gunnison Mill waste containment cell, west portion (top), and a monitoring well to ensure uranium does not leach from cell (bottom). (United States Department of Energy Office of Legacy Management 2012).

References:

Conservation Division Files, USGS (2017). “Elisha Group.” Mineral Resources On-Line Spatial Data, United States Geological Survey (https://mrdata.usgs.gov),

https://mrdata.usgs.gov/mrds/show-mrds.php?dep_id=10013029

Conservation Division Files, USGS (2017). “Pitch Mine.” Mineral Resources On-Line Spatial Data, United States Geological Survey (https://mrdata.usgs.gov),

https://mrdata.usgs.gov/mrds/show-mrds.php?dep_id=10012409

Conservation Division Files, USGS (2017). “Thornburg Mine.” Mineral Resources On-Line Spatial Data, United States Geological Survey (https://mrdata.usgs.gov), https://mrdata.usgs.gov/mrds/show-mrds.php?dep_id=10013146

Conservation Division Files, USGS (2017). “White Earth District.” Mineral Resources On-Line Spatial Data, United States Geological Survey (https://mrdata.usgs.gov), https://mrdata.usgs.gov/mrds/show-mrds.php?dep_id=60000386

Fettus and McKinzie, Nuclear Fuel’s Dirty Beginnings, NRDC (March 2012). https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/uranium-mining-report.pdf

Ford, Bacon, & Davis Utah Incorporated (1981). Engineering assessment of inactive uranium mill tailings: Gunnison site, Gunnison, Colorado. Albuquerque, New Mexico: U.S. Dept. of Energy, UMTRA Project Office, 1981

Google Earth V 9.2.55.2 (2018). Pitch Mine. 38.4075 N, -106.30088 W. Eye alt 3.85 km. Google, Inc. 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018 via https://earth.google.com/web/@38.4075,-106.30088,3147.8244951a,806.44210275d,35y,0h,0t,0r

Hayes, J. D. (1967). A brief history of the Gunnison uranium boom (1954-1962). Gunnison (Colo.), Western State College, 1967.

QKC (2009). “Looking W toward the Los Ocho Mine, Saguache, CO.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Looking_W_toward_the_Los_Ocho_Mine,_Saguache_Co.,_CO_-_panoramio.jpg. Public Domain.

New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources (2018). “Uranium– What is it?” New Mexico Tech, 2018. https://geoinfo.nmt.edu/resources/uranium/what.html

Radioactive Decay, Teach Nuclear (2018), https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/uranium-mining-report.pdf

Tippitt, John, Federal Incentives to Uranium Mining, 27 Rocky Mtn. Law Rev. 457 (1954-55).

United States Department of Energy (1992). Environmental assessment of remedial action at the Gunnison Uranium Mill Tailings Site near Gunnison, Colorado. Final. 1992. United States. doi:10.2172/10150741.

United States Department of Energy (1995). Draft– Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for the Uranium Mill Tailings Remedial Action Ground Water Project. Albuquerque, New Mexico: U.S. Dept. of Energy, 1995.

United States Department of Energy Office of Legacy Management (2012). 2011 UMTRCA Title I Annual Report. Wall Street Journal “Waste Lands” database. Dow Jones & Company, 2012. Accessed March 30, 2018 via http://projects.wsj.com/waste-lands/site/188-gunnison-mill-site/

- Watson and L. Danielson, “Environmental Mediation,” Natural Resources Lawyer vol. 15, no. 4 (1983) pp. 687-723, http://www.sdsg.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/Environmental-Mediation.pdf

Archive

Please click a title to see a description, preview, or to download the document. The files are shown in the order they are added to our library by default. If you would like to sort them in alpha order or reverse alpha order, click on the “Name” title heading once for A-Z or twice for Z-A.

>Back to Document and Materials Index

SEARCH THIS CATEGORY

| Title | Summary | Categories | Link |

|---|

SDSG Sustainable Library

SDSG Sustainable Library